Tagging and Tracking Espionage Botnets

A security researcher who’s spent 18 months cataloging and tracking malicious software that was developed and deployed specifically for spying on governments, activists and industry executives says the complexity and scope of these cyberspy networks now rivals many large conventional cybercrime operations.

Joe Stewart, senior director of malware research at Atlanta-based Dell SecureWorks, said he’s tracked more than 200 unique families of custom malware used in cyber-espionage campaigns. He also uncovered some 1,100 Web site names registered by cyberspies for hosting networks used to control the malware, or for “spear phishing,” highly targeted emails that spread the malware.

Although those numbers may seem low in the grand scheme of things (antivirus companies now deal with many tens of thousands of new malware samples each day), almost everything about the way these cyberspying networks are put together seems designed to mask the true scope of the operations, he found. For instance, Stewart discovered that the attackers set up almost 20,000 subdomains on those 1,100 domain names; but these subdomains were used for controlling or handing out new malware for botnets that each only controlled a few hundred computers at a time.

Although those numbers may seem low in the grand scheme of things (antivirus companies now deal with many tens of thousands of new malware samples each day), almost everything about the way these cyberspying networks are put together seems designed to mask the true scope of the operations, he found. For instance, Stewart discovered that the attackers set up almost 20,000 subdomains on those 1,100 domain names; but these subdomains were used for controlling or handing out new malware for botnets that each only controlled a few hundred computers at a time.

“Unlike the largest cybercrime networks that can contain millions of infected computers in a single botnet, cyber-espionage encompasses tens of thousands of infected computers spread across hundreds of botnets,” Stewart wrote in a paper released at last week’s Black Hat security convention in Las Vegas. “So each botnet…tends to look like a fairly small-scale operation. But this belies the fact that for every [cyber-espionage] botnet that is discovered and publicized, hundreds more continue to lie undetected on thousands of networks.”

Once you get past all the technical misdirection built into the malware networks by its architects, Stewart said, the infrastructure that frames these spy machines generally points in one of two directions: one group’s infrastructure points back to Shanghai, the other to Beijing.

“There have to be hundreds of people involved, just to maintain this amount of infrastructure and this much activity and this many spear phishes, collecting so many documents, and writing this much malware,” Stewart said. “But when it comes time to grouping them, that’s when it gets harder. What I can tell from the clustering I’m doing here is that there are two major groups in operation. Some have dozens of different malware families that they use, but many will share a common botnet command and control infrastructure.”

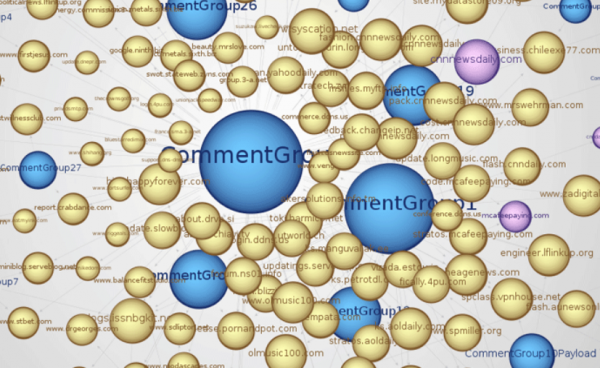

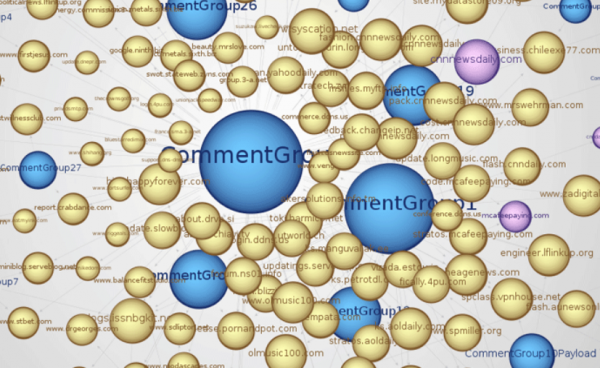

Domains connected to different cyber-espionage botnets typically trace back to one of two destinations in China, according to Dell SecureWorks.

Domains connected to different cyber-espionage botnets typically trace back to one of two destinations in China, according to Dell SecureWorks.

I also attended Black Hat (co-keynoting with novelist Neal Stephenson on Thursday morning); Prior to that, I spent a little over an hour interviewing Stewart about his research. Excerpts from that interview are below.

BK: The report you just released describes a number of malware attacks that appear to be different attacks, but which share some pretty common characteristics. In your view, is there a marked diversity in these malware samples, or are they pretty uniform?

Stewart: It’s more different implementations of the same thing over and over again. There are not a lot of features or widely varying techniques. It’s as if you went into a computer programming class and gave an assignment, and said your malware should do this and this, and everyone pumps out a tiny little program that does that, and you have 20 different malware samples that none of the antivirus programs are going to detect. While they might share a few subroutines — the bulk of the malicious programs appear to be different source code, communicate differently — but essentially they are the same thing: There will be some sort of backdooor and downloader, and then some kind of obfuscation of traffic so that it’s not transferred in plain text. Occasionally, it will use SSL, but not very often.

BK: How about the detection? It seems the detection for this type of malware is pretty low, is that right?

Stewart: Yep. But it’s strictly because they are being developed custom to this purpose and distributed in low numbers. They’re not often packed with conventional packers, because that in itself is often suspicious. If they have any obfuscation at all, it’s [to alter] the code by one byte and load it in with a minimal decryption stub.

BK: How often do you get a chance to see the method of delivery for a given attack that you’re tracking?

Stewart: Maybe 5-10 percent of the time. A lot of the intel we build up is simply from seeing a spear phish and the accompanying document that’s infected. We look at the host names involved, the IP addresses used, then we go out and try to find other malware samples that talk to those same IPs or domains, or another domain with the same registrant. Then we pull in those samples out of malware feeds and public sandboxes, and run them and see where they try to connect with. And when you repeat that process over and over, it becomes one big feedback loop.

BK: You said in your paper that there are many thousands of other DNS names you are tracking but for which you had no accompanying malware samples. How does that happen?

Stewart: My suspicion is that those samples are not being detected or not shared with the antivirus companies.

BK: But how is it that you know to track DNS names you believe are related?

Stewart: Because these guys are trying to save a little bit of work. Instead of registering a new domain for every piece of malware deployed, they’ll just use the same domain for number of years, and have several dozen or more subdomains for that, which will each act as a new command and control point for different malware. Then we can use things like passive DNS to find other subdomains that might be hiding under that domain, and we can reach out and find other malware samples that are related. But like I said, 90 percent of the time, we don’t find that malware sample. We know that domain was specifically created by a [cyber espionage] actor for command and control, and we track it to see what else is related to that IP, but we don’t often come across the malware sample.

The truth is that if we if we graphed all of this activity, you wouldn’t be able to view each part without the whole thing literally covering all the walls of my office. I’ve got them all tracked, but If I try to draw them all for you, it’s a big mess. So what we did with this graph is just to take the malware we know about and have in hand, and to show you how that’s related to other IPs and domains and subdomains. That graphic in our paper probably represents about 10 percent of what we know about.

BK: What do you think is the reason for all of these small, but ultimately interconnected [cyber espionage] operations or botnets? Is it a strength in numbers thing, or is it more likely that there are multiple groups doing their own thing and only later joining forces?

Stewart: I feel like there are multiple groups doing their own thing, and then in those, there are probably different actors that have different preferences for how they conduct operations. Some actors just don’t like domains and just want to host it on some IP somewhere. Everyone has their own method of operation and they don’t all follow the same manual. But we know that many of them do share resources, because scale of the activity we see coming out of these two major groups…I would find it hard to believe that there are just a small number of people writing all that malware and controlling all those domains and IPs.

BK: Given the access that you have, is there a way to extrapolate how much data is being exfiltrated?

Stewart: I don’t have any access, except for the sinkholing operations. Once you do that, you remove their ability to go ahead and exfiltrate. All the graphing and stuff I’m doing to map the actor side is being done through malware samples, passive DNS and the victim data is connected to the sink holing, but that doesn’t tell me what data they’re stealing or how much of it they’re stealing.

BK: You mentioned at the end of the paper an example of what looks like an overlap between traditional financially-oriented cybercrime and that of state-sponsored activity. Are you really seeing that much overlap?

Stewart: I think we are. It’s not something where there have been a lot of public reports about it. But we’ve certainly seen spearphishes using malware that we haven’t seen in prior [cyber espionage] stuff. The payloads look a lot more like conventional Eastern European cybercrime, but the spear phish email looks much more like what you’d expect to see coming from Chinese actors. And obviously, the overlap we’ve seen for a while now too, the exploits work their way from zero-day targeted attacks, and then turn around a few weeks later and that same exploit is now in BlackHole exploit kit.

BK: But that hasn’t changed over the years has it?

Stewart: I think so. In terms of the exploit coming from one side and flowing into the other. We used to see more exploits developed by exploit kit authors or someone paid to put these attack tools in exploit kits, and then on the other side, the espionage actors using older exploits. But at some point, it shifted and zero-days started to be developed by the [espionage] actors. After all, why should the financially-oriented attackers invest all that time and research when these other espionage actors were coming up with some really good stuff?

BK: And do you see any changes in the use of zero-days in these attacks? Last time I checked it was mostly exploits for which there were patches already available.

Stewart: So they use ‘em when they got ‘em. Lately they’ve had the XML Core Services stuff, which has gotten them a lot of mileage. But they don’t stop operations just because they don’t have a zero-day.

BK: Do you have any knowledge of what the cyber-espionage actors are doing to keep the malware that’s on the victim systems from being detected by antivirus tools?

Stewart: I haven’t seen any signs of that. A lot of this malware doesn’t have any update feature at all. But then again I don’t do the long-term monitoring of these malware samples like I used to do with a lot of the spam bots. It’s a little bit harder to fool a real live actor who has a botnet of maybe 10 machines. It’s a little harder to blend in there without being noticed. They can quickly determine who’s in the environment that they’re not interested in and just delete the code from that host machine.

BK: As far as these subdomains and overarching control domains go, is that changing at all, or are the attackers still hammering the dynamic DNS providers over and over again?

Stewart: It’s a dynamic mix of dynamic DNS and actively registered domains, and it all comes down to the preferences of the groups and what they like to use. They may not have as much success with some targets who are used to being hit for years and have just blocked all dynamic DNS providers within their networks, and in those cases the attackers are forced to go with some kind of hard-coded IPs or registering their own domains. So we’re seeing a pretty equal mix.

BK: So what’s your best guess of the number of distinct groups or actors here?

Stewart: Well, it seems there are two main groups, but you’ve got a lot of other activity which seems tangentially related. Sometimes it’s just a slight connection — an overlapped IP in the past and there’s some shared code — but they don’t overlap so much with those two groups. And the other collections of malware…we see them in spear phishes and they’re going after the same targets, and they don’t have any overlap with other groups’ infrastructure whatsoever. So from the way we’re approaching the problem trying to map them out by network touch points and domain registrations, it’s impossible to tell.

But it’s pretty clear there are two main groups, very large and active. Then there’s a lot of other activity that coalesces into clusters, but yet we can’t say that’s not two different actors in the same group versus two independent actors who don’t know each other. So I don’t think anyone can tell you the answer to the question without having legal means to infiltrate these networks, and without having the ability to spy on them and see who’s calling the shots and paying the payroll, but we obviously don’t have the legal ability to do that.

BK: Is hacking back at these guys really illegal?

Stewart: I’m talking about penetrating their networks and spying on where they’re located and their computers and emails. We’ve seen some glimpses of that and leaks in the media from Hardcore Charlie, but I don’t know how credible that is. There was a hacker who released some things on Pastebin who said he’d hacked into a Chinese defense contractor, and he found documents in there outlining their cyber espionage activities, and was somehow tied to Vietnam and some Ukrainian people who were supplying information on U.S. troop movements to the Taliban. My main problem with this information was that it was all supplied in English.

BK: Are you seeing any indication that these attacks are targeting other countries, with the fingerprint of China?

Stewart: Not sure what you’re asking.

BK: People typically assume that the target of these attacks are the U.S. and some of the countries in the Asian region…

Stewart: Yeah, we’re seeing European government entities, Asia and certainly India. The only place I don’t see a lot of activity against is South America. But obviously it seems to be happening there. We heard the whole thing about how the malware was stealing the CAD designs from the company in Peru, right? So it seems to be happening there as well. So it’s pretty much anyone can be a target. You just have to have something they want.

BK: Are you seeing these espionage attacks and the sources tracing back to sources outside of China?

Stewart: Sure. We talked a bit in the paper about one that seems to have been coming from on security company in another Asian nation. But you can kind of tell when you see something that doesn’t completely match the modus operandi.

BK: Can you share the information about which company you’re referencing?

Stewart: We cannot. If law enforcement is interested in that information, we’re happy to share it.

BK: Are you seeing any indication that the antivirus companies are doing better job detecting this stuff?

Stewart: I think some security companies are definitely doing a better job of incorporating protections into their services or products. I don’t know if AV companies are necessarily getting better detection rates, but certainly a lot of companies we’re working with to share information about malware samples and IP addresses are classifying them to incorporate them into detections.

BK: Would you say the activity you’ve measured is just a better understanding that you’ve gained as to the true scope of the problem, or has the problem of state-sponsored espionage gotten more pronounced over the last few years?

Stewart: I think it’s a better understanding. This kind of methodical effort to classify things and separate all of the regular financial malware from the cyber espionage stuff…the samples have shown up on different AV radars over the years. The problem is that there’s just not enough work put into classifying these things so that when we see it again we know what it is. In a lot of these attacks, the next time a piece of malware is detected it has a different name and nobody connects the two. And if I don’t see it on the AV networks with a proper and consistent name, we’ll assign it our own name and call it that going forward. That’s what I’ve been trying to do — eliminate the mystery.

BK: A lot of financially-oriented malware attacks are fairly automated, in that they rely on tools that handle much of the exploitation, and in some cases even the extraction of funds from victim systems. But these state-sponsored attacks tend to be quite a bit more hands-on, don’t they?

Stewart: It’s something where it only works on a human scale for them. It’s not something like cyber crime botnets where they can leverage as many computers as they can pay to have infected. Someone’s got to craft these spear phishes and send them out, and someone has to deal with the documents that are stolen in these operations. They can only get as big as the number of people they have to train and perform these operations. My worry is not that these entities or groups are going to get huge and have lots of more targets, but that there are going to be more and more players that will get into the game because they realize that nobody is getting prosecuted for this and as long as they don’t cross certain lines within our own jurisdiction, they seem pretty free to spy on other companies and other countries. Why not have a contract doing this activity for the government and then on the side make some money doing it for private companies? Then they have some kind of legal shield, because the government can’t come and prosecute them, because they’re doing the same activity for the government. That’s my worry: That we’re going to see a lot more players in this space.

BK: So really, you’re thinking down the road a bit as this becomes a bit more commoditized?

Stewart: Yeah, I guess. Not that they’ll necessarily be advertising this – that they’ll put up an ad at [the RSA Security Conference] and say “We’ll spy on your competitors” — but certainly you can see some enterprising businesses with ties to the government being able to conceive of such a plan and make some pretty good money doing it.

BK: Are you seeing evidence of that activity so far?

Stewart: I think that’s what that security company we wrote about in the report is doing. Based on the targets. Because on the one hand we see them going after foreign militaries, and then also going after commercial targets, and journalists within the same country. And then we ask, ‘Well, why would they be interested in them?,” and then we see those journalists are publishing a news magazine that’s critical of that government.

BK: Can you be more specific about the company that you’ve seen doing this?

Stewart: No.

BK: But pretty much all of those nations have tens of millions of people and millions of businesses…so what’s the harm in naming the country where the allegedly offending company resides?

Stewart: Yes, but they’ve only got so many security companies, and probably only so many companies that also offer ethical hacking courses. But they are an ally of the United States. One of the targets that we saw and alerted was Japan, and I think it was today that the finance minster there went to the news media and notified folks that they suffered a breach. We don’t know if it’s the same thing that we notified them about, but there it is.

For those of you still reading this far, I’d like to apologize for the site issues that many readers experienced last week. My site has been the targeted of sustained and sadly escalating distributed denial-of-service attacks for nearly a week now. I’ve been working with anti-DDoS firm Prolexic to help mitigate the attacks, which seems to be helping quite a bit. Expect a full post-mortem on the assaults as more information becomes available.

rtechinsane,icodesource,SEO,SEO Tips,SEO Backlinks,SEO content,SEO tricks,SEO Engine,codes,gadgets,iphones,ipad,4G phones,geeks,reviews,database,DBMS,

warehouse,datamining,datawarehouse

Joe Stewart, senior director of malware research at Atlanta-based Dell SecureWorks, said he’s tracked more than 200 unique families of custom malware used in cyber-espionage campaigns. He also uncovered some 1,100 Web site names registered by cyberspies for hosting networks used to control the malware, or for “spear phishing,” highly targeted emails that spread the malware.

Although those numbers may seem low in the grand scheme of things (antivirus companies now deal with many tens of thousands of new malware samples each day), almost everything about the way these cyberspying networks are put together seems designed to mask the true scope of the operations, he found. For instance, Stewart discovered that the attackers set up almost 20,000 subdomains on those 1,100 domain names; but these subdomains were used for controlling or handing out new malware for botnets that each only controlled a few hundred computers at a time.

Although those numbers may seem low in the grand scheme of things (antivirus companies now deal with many tens of thousands of new malware samples each day), almost everything about the way these cyberspying networks are put together seems designed to mask the true scope of the operations, he found. For instance, Stewart discovered that the attackers set up almost 20,000 subdomains on those 1,100 domain names; but these subdomains were used for controlling or handing out new malware for botnets that each only controlled a few hundred computers at a time.“Unlike the largest cybercrime networks that can contain millions of infected computers in a single botnet, cyber-espionage encompasses tens of thousands of infected computers spread across hundreds of botnets,” Stewart wrote in a paper released at last week’s Black Hat security convention in Las Vegas. “So each botnet…tends to look like a fairly small-scale operation. But this belies the fact that for every [cyber-espionage] botnet that is discovered and publicized, hundreds more continue to lie undetected on thousands of networks.”

Once you get past all the technical misdirection built into the malware networks by its architects, Stewart said, the infrastructure that frames these spy machines generally points in one of two directions: one group’s infrastructure points back to Shanghai, the other to Beijing.

“There have to be hundreds of people involved, just to maintain this amount of infrastructure and this much activity and this many spear phishes, collecting so many documents, and writing this much malware,” Stewart said. “But when it comes time to grouping them, that’s when it gets harder. What I can tell from the clustering I’m doing here is that there are two major groups in operation. Some have dozens of different malware families that they use, but many will share a common botnet command and control infrastructure.”

Domains connected to different cyber-espionage botnets typically trace back to one of two destinations in China, according to Dell SecureWorks.

Domains connected to different cyber-espionage botnets typically trace back to one of two destinations in China, according to Dell SecureWorks.I also attended Black Hat (co-keynoting with novelist Neal Stephenson on Thursday morning); Prior to that, I spent a little over an hour interviewing Stewart about his research. Excerpts from that interview are below.

BK: The report you just released describes a number of malware attacks that appear to be different attacks, but which share some pretty common characteristics. In your view, is there a marked diversity in these malware samples, or are they pretty uniform?

Stewart: It’s more different implementations of the same thing over and over again. There are not a lot of features or widely varying techniques. It’s as if you went into a computer programming class and gave an assignment, and said your malware should do this and this, and everyone pumps out a tiny little program that does that, and you have 20 different malware samples that none of the antivirus programs are going to detect. While they might share a few subroutines — the bulk of the malicious programs appear to be different source code, communicate differently — but essentially they are the same thing: There will be some sort of backdooor and downloader, and then some kind of obfuscation of traffic so that it’s not transferred in plain text. Occasionally, it will use SSL, but not very often.

BK: How about the detection? It seems the detection for this type of malware is pretty low, is that right?

Stewart: Yep. But it’s strictly because they are being developed custom to this purpose and distributed in low numbers. They’re not often packed with conventional packers, because that in itself is often suspicious. If they have any obfuscation at all, it’s [to alter] the code by one byte and load it in with a minimal decryption stub.

BK: How often do you get a chance to see the method of delivery for a given attack that you’re tracking?

Stewart: Maybe 5-10 percent of the time. A lot of the intel we build up is simply from seeing a spear phish and the accompanying document that’s infected. We look at the host names involved, the IP addresses used, then we go out and try to find other malware samples that talk to those same IPs or domains, or another domain with the same registrant. Then we pull in those samples out of malware feeds and public sandboxes, and run them and see where they try to connect with. And when you repeat that process over and over, it becomes one big feedback loop.

BK: You said in your paper that there are many thousands of other DNS names you are tracking but for which you had no accompanying malware samples. How does that happen?

Stewart: My suspicion is that those samples are not being detected or not shared with the antivirus companies.

BK: But how is it that you know to track DNS names you believe are related?

Stewart: Because these guys are trying to save a little bit of work. Instead of registering a new domain for every piece of malware deployed, they’ll just use the same domain for number of years, and have several dozen or more subdomains for that, which will each act as a new command and control point for different malware. Then we can use things like passive DNS to find other subdomains that might be hiding under that domain, and we can reach out and find other malware samples that are related. But like I said, 90 percent of the time, we don’t find that malware sample. We know that domain was specifically created by a [cyber espionage] actor for command and control, and we track it to see what else is related to that IP, but we don’t often come across the malware sample.

The truth is that if we if we graphed all of this activity, you wouldn’t be able to view each part without the whole thing literally covering all the walls of my office. I’ve got them all tracked, but If I try to draw them all for you, it’s a big mess. So what we did with this graph is just to take the malware we know about and have in hand, and to show you how that’s related to other IPs and domains and subdomains. That graphic in our paper probably represents about 10 percent of what we know about.

BK: What do you think is the reason for all of these small, but ultimately interconnected [cyber espionage] operations or botnets? Is it a strength in numbers thing, or is it more likely that there are multiple groups doing their own thing and only later joining forces?

Stewart: I feel like there are multiple groups doing their own thing, and then in those, there are probably different actors that have different preferences for how they conduct operations. Some actors just don’t like domains and just want to host it on some IP somewhere. Everyone has their own method of operation and they don’t all follow the same manual. But we know that many of them do share resources, because scale of the activity we see coming out of these two major groups…I would find it hard to believe that there are just a small number of people writing all that malware and controlling all those domains and IPs.

BK: Given the access that you have, is there a way to extrapolate how much data is being exfiltrated?

Stewart: I don’t have any access, except for the sinkholing operations. Once you do that, you remove their ability to go ahead and exfiltrate. All the graphing and stuff I’m doing to map the actor side is being done through malware samples, passive DNS and the victim data is connected to the sink holing, but that doesn’t tell me what data they’re stealing or how much of it they’re stealing.

BK: You mentioned at the end of the paper an example of what looks like an overlap between traditional financially-oriented cybercrime and that of state-sponsored activity. Are you really seeing that much overlap?

Stewart: I think we are. It’s not something where there have been a lot of public reports about it. But we’ve certainly seen spearphishes using malware that we haven’t seen in prior [cyber espionage] stuff. The payloads look a lot more like conventional Eastern European cybercrime, but the spear phish email looks much more like what you’d expect to see coming from Chinese actors. And obviously, the overlap we’ve seen for a while now too, the exploits work their way from zero-day targeted attacks, and then turn around a few weeks later and that same exploit is now in BlackHole exploit kit.

BK: But that hasn’t changed over the years has it?

Stewart: I think so. In terms of the exploit coming from one side and flowing into the other. We used to see more exploits developed by exploit kit authors or someone paid to put these attack tools in exploit kits, and then on the other side, the espionage actors using older exploits. But at some point, it shifted and zero-days started to be developed by the [espionage] actors. After all, why should the financially-oriented attackers invest all that time and research when these other espionage actors were coming up with some really good stuff?

BK: And do you see any changes in the use of zero-days in these attacks? Last time I checked it was mostly exploits for which there were patches already available.

Stewart: So they use ‘em when they got ‘em. Lately they’ve had the XML Core Services stuff, which has gotten them a lot of mileage. But they don’t stop operations just because they don’t have a zero-day.

BK: Do you have any knowledge of what the cyber-espionage actors are doing to keep the malware that’s on the victim systems from being detected by antivirus tools?

Stewart: I haven’t seen any signs of that. A lot of this malware doesn’t have any update feature at all. But then again I don’t do the long-term monitoring of these malware samples like I used to do with a lot of the spam bots. It’s a little bit harder to fool a real live actor who has a botnet of maybe 10 machines. It’s a little harder to blend in there without being noticed. They can quickly determine who’s in the environment that they’re not interested in and just delete the code from that host machine.

BK: As far as these subdomains and overarching control domains go, is that changing at all, or are the attackers still hammering the dynamic DNS providers over and over again?

Stewart: It’s a dynamic mix of dynamic DNS and actively registered domains, and it all comes down to the preferences of the groups and what they like to use. They may not have as much success with some targets who are used to being hit for years and have just blocked all dynamic DNS providers within their networks, and in those cases the attackers are forced to go with some kind of hard-coded IPs or registering their own domains. So we’re seeing a pretty equal mix.

BK: So what’s your best guess of the number of distinct groups or actors here?

Stewart: Well, it seems there are two main groups, but you’ve got a lot of other activity which seems tangentially related. Sometimes it’s just a slight connection — an overlapped IP in the past and there’s some shared code — but they don’t overlap so much with those two groups. And the other collections of malware…we see them in spear phishes and they’re going after the same targets, and they don’t have any overlap with other groups’ infrastructure whatsoever. So from the way we’re approaching the problem trying to map them out by network touch points and domain registrations, it’s impossible to tell.

But it’s pretty clear there are two main groups, very large and active. Then there’s a lot of other activity that coalesces into clusters, but yet we can’t say that’s not two different actors in the same group versus two independent actors who don’t know each other. So I don’t think anyone can tell you the answer to the question without having legal means to infiltrate these networks, and without having the ability to spy on them and see who’s calling the shots and paying the payroll, but we obviously don’t have the legal ability to do that.

BK: Is hacking back at these guys really illegal?

Stewart: I’m talking about penetrating their networks and spying on where they’re located and their computers and emails. We’ve seen some glimpses of that and leaks in the media from Hardcore Charlie, but I don’t know how credible that is. There was a hacker who released some things on Pastebin who said he’d hacked into a Chinese defense contractor, and he found documents in there outlining their cyber espionage activities, and was somehow tied to Vietnam and some Ukrainian people who were supplying information on U.S. troop movements to the Taliban. My main problem with this information was that it was all supplied in English.

BK: Are you seeing any indication that these attacks are targeting other countries, with the fingerprint of China?

Stewart: Not sure what you’re asking.

BK: People typically assume that the target of these attacks are the U.S. and some of the countries in the Asian region…

Stewart: Yeah, we’re seeing European government entities, Asia and certainly India. The only place I don’t see a lot of activity against is South America. But obviously it seems to be happening there. We heard the whole thing about how the malware was stealing the CAD designs from the company in Peru, right? So it seems to be happening there as well. So it’s pretty much anyone can be a target. You just have to have something they want.

BK: Are you seeing these espionage attacks and the sources tracing back to sources outside of China?

Stewart: Sure. We talked a bit in the paper about one that seems to have been coming from on security company in another Asian nation. But you can kind of tell when you see something that doesn’t completely match the modus operandi.

BK: Can you share the information about which company you’re referencing?

Stewart: We cannot. If law enforcement is interested in that information, we’re happy to share it.

BK: Are you seeing any indication that the antivirus companies are doing better job detecting this stuff?

Stewart: I think some security companies are definitely doing a better job of incorporating protections into their services or products. I don’t know if AV companies are necessarily getting better detection rates, but certainly a lot of companies we’re working with to share information about malware samples and IP addresses are classifying them to incorporate them into detections.

BK: Would you say the activity you’ve measured is just a better understanding that you’ve gained as to the true scope of the problem, or has the problem of state-sponsored espionage gotten more pronounced over the last few years?

Stewart: I think it’s a better understanding. This kind of methodical effort to classify things and separate all of the regular financial malware from the cyber espionage stuff…the samples have shown up on different AV radars over the years. The problem is that there’s just not enough work put into classifying these things so that when we see it again we know what it is. In a lot of these attacks, the next time a piece of malware is detected it has a different name and nobody connects the two. And if I don’t see it on the AV networks with a proper and consistent name, we’ll assign it our own name and call it that going forward. That’s what I’ve been trying to do — eliminate the mystery.

BK: A lot of financially-oriented malware attacks are fairly automated, in that they rely on tools that handle much of the exploitation, and in some cases even the extraction of funds from victim systems. But these state-sponsored attacks tend to be quite a bit more hands-on, don’t they?

Stewart: It’s something where it only works on a human scale for them. It’s not something like cyber crime botnets where they can leverage as many computers as they can pay to have infected. Someone’s got to craft these spear phishes and send them out, and someone has to deal with the documents that are stolen in these operations. They can only get as big as the number of people they have to train and perform these operations. My worry is not that these entities or groups are going to get huge and have lots of more targets, but that there are going to be more and more players that will get into the game because they realize that nobody is getting prosecuted for this and as long as they don’t cross certain lines within our own jurisdiction, they seem pretty free to spy on other companies and other countries. Why not have a contract doing this activity for the government and then on the side make some money doing it for private companies? Then they have some kind of legal shield, because the government can’t come and prosecute them, because they’re doing the same activity for the government. That’s my worry: That we’re going to see a lot more players in this space.

BK: So really, you’re thinking down the road a bit as this becomes a bit more commoditized?

Stewart: Yeah, I guess. Not that they’ll necessarily be advertising this – that they’ll put up an ad at [the RSA Security Conference] and say “We’ll spy on your competitors” — but certainly you can see some enterprising businesses with ties to the government being able to conceive of such a plan and make some pretty good money doing it.

BK: Are you seeing evidence of that activity so far?

Stewart: I think that’s what that security company we wrote about in the report is doing. Based on the targets. Because on the one hand we see them going after foreign militaries, and then also going after commercial targets, and journalists within the same country. And then we ask, ‘Well, why would they be interested in them?,” and then we see those journalists are publishing a news magazine that’s critical of that government.

BK: Can you be more specific about the company that you’ve seen doing this?

Stewart: No.

BK: But pretty much all of those nations have tens of millions of people and millions of businesses…so what’s the harm in naming the country where the allegedly offending company resides?

Stewart: Yes, but they’ve only got so many security companies, and probably only so many companies that also offer ethical hacking courses. But they are an ally of the United States. One of the targets that we saw and alerted was Japan, and I think it was today that the finance minster there went to the news media and notified folks that they suffered a breach. We don’t know if it’s the same thing that we notified them about, but there it is.

For those of you still reading this far, I’d like to apologize for the site issues that many readers experienced last week. My site has been the targeted of sustained and sadly escalating distributed denial-of-service attacks for nearly a week now. I’ve been working with anti-DDoS firm Prolexic to help mitigate the attacks, which seems to be helping quite a bit. Expect a full post-mortem on the assaults as more information becomes available.

rtechinsane,icodesource,SEO,SEO Tips,SEO Backlinks,SEO content,SEO tricks,SEO Engine,codes,gadgets,iphones,ipad,4G phones,geeks,reviews,database,DBMS,

warehouse,datamining,datawarehouse

0 comments:

Post a Comment